African American History in Germany

VASSAR TODAY

A Breath of Freedom: African American GIs in Germany

By Beth Trickett

“I talked to a black soldier’s son who was born in Germany. His German mother and American father fell in love and got married in Germany during the late 1940s. But as soon as they got back on the boat to America, they were immediately segregated into white and black sections. As a child, the son never understood why the family had to travel at night to avoid being attacked just because his parents were an interracial couple. They could never stay together in a hotel as a family or go out to eat. He felt abandoned because his mother was always leaving to stay in a ‘white hotel’ and he questioned if she really loved him.”

“This story is heartbreaking,” continues Maria Höhn, associate professor of history, who has spent the past fifteen years immersed in the stories of African American troops stationed in post-war Germany and the recollections of their family members.

Nearly three million African Americans have served inGermany since 1945, yet little is known about their experience abroad. Höhn, who was raised in Germany, published her book GIs and Frauleins: The German-American Encounter in 1950s West Germany in 2002—it was the first of its kind to examine the experiences of black soldiers. When Höhn began her research in Germany, she found it ironic that “African Americans mainly had a positive experience in Germany because there were no Jim Crow laws and they could enter any store or restaurant and even fall in love with white women.” Colin Powell described his military experience there in 1958 as “a breath of freedom. ”Höhn says, “In turn, the soldiers came home to fight for civil rights, but they also inspired Germans to engage in civil rights issues.”

Soon after publishing her book, she met fellow historian Martin Klimke, of the German Historical Institute (GHI) in Washington, D.C., and the Heidelberg Center for American Studies at the University of Heidelberg, who shared an interest in this research. The two decided to work together to build a free research database for students and teachers around the world. “The Civil Rights Struggle, African American GIs, and Germany” contains digitized documents from the Archive for Soldiers’ Rights in Berlin and from the private collections of former civil rights activists, as well as photographs, audio-visual sources and transcripts, newspapers, posters, flyers, governmental records, and the oral histories of African American service personnel.

Students at Vassar and Heidelberg University also contributed to the project, uncovering photos and other materials and conducting video interviews with African American veterans to add to the database. “They found absolutely amazing materials,” notes Höhn. “The project shows them that you can still discover sources and stories of the past that no one knows anything about.”

In 2008,Höhn and Klimke were asked by the Humanities Council in Washington, D.C., to contribute to a citywide commemoration of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s death and to celebrate his global legacy. Höhn and Klimke compiled a selection of previously unseen images (including four cartoons uncovered by students during their research) that documented King’s visit to West and East Berlin in 1964, but also included images of black GIs.

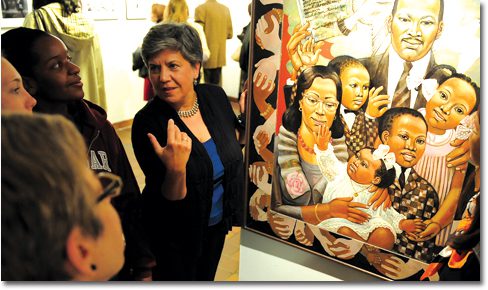

During the project’s exhibition on campus in October, Höhn shows a painting of

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and family by East German artist Susanne Kandt-Horn.

“We were immensely proud of the exhibit, but were completely unprepared for the public response,” says Höhn. The show and research project was reviewed in a U.S. military magazine and in a major German newspaper, and the exposure led to an outpouring of requests for lectures, workshops, and a traveling photo exhibition in the U.S. and Germany. The project also captured the attention of the NAACP, which honored Höhn and Klimke with its 2009 Julius E. Williams Distinguished Community Service Award.

Throughout the month of October 2009, Höhn had the opportunity to share materials gathered for the documentary project with the Vassar community in a Palmer Gallery exhibition. Many of the photographs illustrated the relative freedom that black soldiers experienced in a post-war

Germany. One highlight of the exhibition was a recording of a sermon delivered by Martin Luther King, Jr. during the Cold War at a packed Saint Mary’s Church in East Berlin. According to church representative Roland Stolte, King became a highly revered figure in East Germany after the 1964 speech (of which most Americans have no knowledge) because he gave citizens hope during a difficult time in the country’s history. The exhibition is scheduled to travel to additional U.S. and European destinations this year.

In October, Vassar also hosted a five-day international conference, titled “African American Civil Rights and Germany in the 20th Century.” The conference brought together civil rights, history and political scholars, including Angela Davis, whose keynote address focused on her experience in Germany while a student there in the 1960s and the Germans’ surprising solidarity with the U.S. civil rights movement. Presentations ranged from “Black Soldiers, Germans, and World War II” to “Jazz and Civil Rights in a Divided Germany,” the latter concluding with a piano performance by Vassar music professor Brian Mann. Vassar and GHI organized both the gallery show and the conference.

Despite the success of the project, Höhn’s objective has remained the same: to capture and preserve these stories before they are lost to history. She’s even been working with Poughkeepsie and Arlington high schools to incorporate some aspects of the conference and the digital archive into the curricula there.

“We see [the archive] as a democratic tool,” says Höhn; she is hopeful it will find its way to a broader audience.

For more information on Höhn and Klimke’s documentary project, visit www.aacvr-germany.org.

—Beth Trickett

Photo Credits: National Archives and Records Administration; Buck Lewis